BY DESMOND BOLLERS

A wise person once said, “The most effective way to destroy a people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.”

This quotation is frequently erroneously attributed to George Orwell, but regardless of who first penned, or uttered these words, this represents the approach that was utilized by the European colonialists in the Caribbean against the Native American and African-descendant peoples with great success. In fact, they were so successful that even today there are people in the Caribbean who are unwilling to learn about or are ashamed of their history.

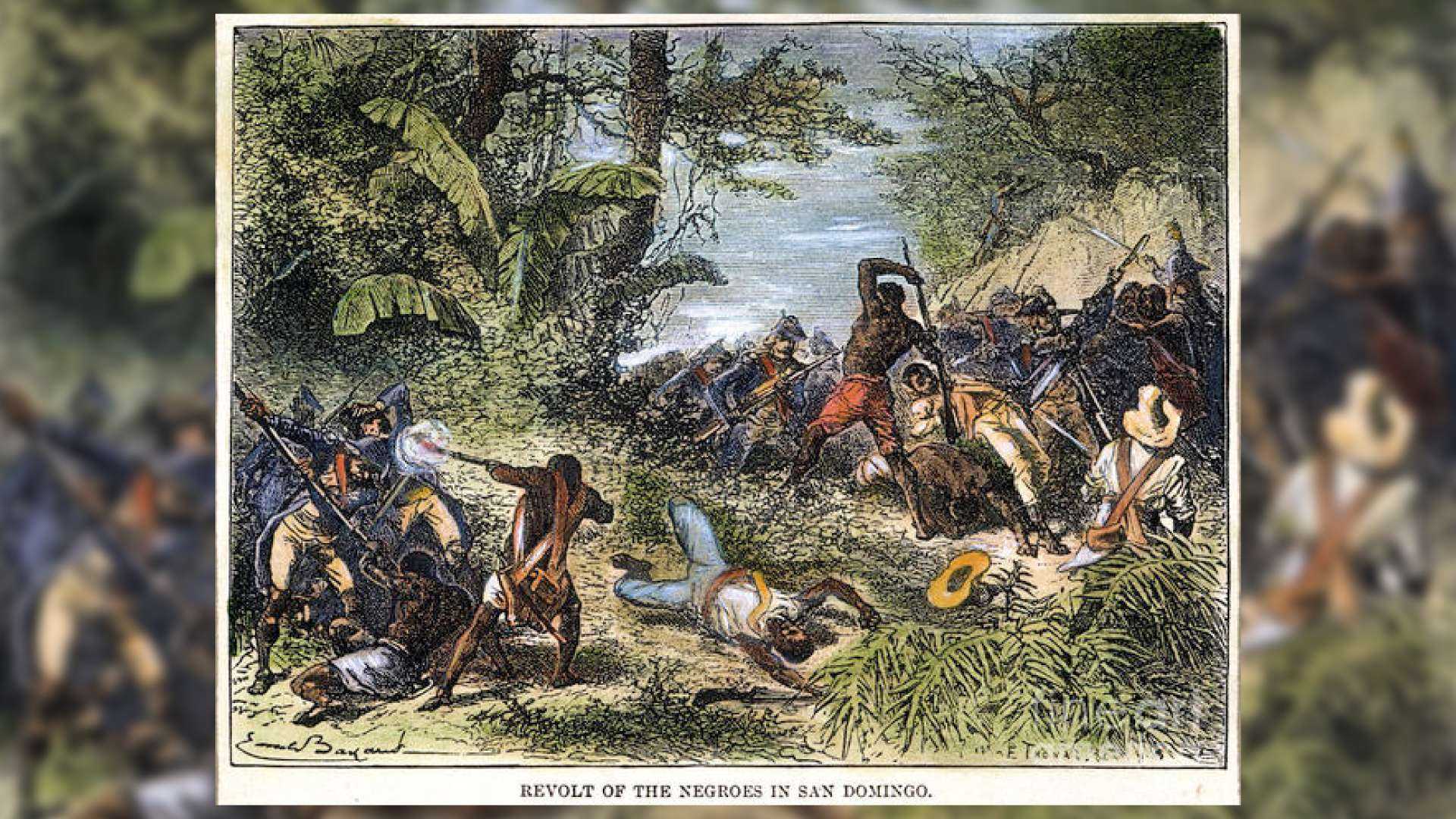

When it comes to the history of their colonial possessions, including the Caribbean, the colonial masters have practiced and perfected what I refer to as ‘The Three Ds’ – Deny, Diminish, Distort. They deny our ancestors’ achievements when they can. When they are unable to deny those accomplishments, they diminish them and when they can’t diminish them, they resort to distortion causing us to feel embarrassed about our history and to question whether enslaved Africans who revolted were heroes or villains.

The history textbooks would have us believe that when the Spaniards arrived, the ‘peaceful’ Tainos of the Greater Antilles simply wilted and allowed themselves to be dispossessed of their lands, subjugated, enslaved, sexually exploited and finally wiped out without putting out a fight. Nothing could be farther from the truth. The Tainos fought valiantly, but their weapons were no match for the superior Spanish military weaponry. I am sure you are familiar with the saying ‘Don’t bring a knife to a gunfight. Well, the Tainos brought bows and arrows, spears and wooden clubs to a fight against men covered in metal armour and armed with cannon and muskets, so the eventual outcome was inevitable.

Among the many other examples of denying in the Caribbean is the 1831 Christmas Rebellion in western Jamaica led by Sam Sharpe. Despite this being the largest revolt by enslaved Africans anywhere in the Americas, for almost a century and a half it was never mentioned in history textbooks that were used in schools in the Caribbean. Similarly, the 1816 rebellion in Barbados led by Bussa, which was the second largest revolt by enslaved Africans anywhere in the Americas, was left off the pages of West Indian history texts. In the USA the 1811 German Coast uprising in Louisiana led by Charles Deslondes which was the largest rebellion by enslaved Africans in North America, was largely unknown by Americans until quite recently as it was never mentioned in textbooks.

When it comes to diminishing, the colonials were equally adept. The impact that the Haitian Revolution had on the history of the Americas is consistently downplayed and almost never mentioned. US history books generally don’t mention that it was the Haitian defeat of the French in St. Domingue that convinced Napoleon to sell the much less valuable Louisiana Territory to the fledgling United States, in effect doubling its size and paving the way for ‘manifest destiny,’ enabling the US to extend ‘From sea to shining sea.’

The 1823 rebellion by enslaved Africans in British Guiana led by Quamina and Jack Gladstone was the third largest revolt by enslaved Africans anywhere in the Americas, yet their leading role was diminished, and the focus was placed on an English minister of religion named John Smith. In fact, his only role was to try and persuade the freedom fighters not to rebel. The Great Berbice Uprising of 1763 led by Kofi was the first attempt to establish an independent republic anywhere in the Americas preceding the formation of the USA by thirteen years, yet this fact is excluded from history texts.

Next edition, we are going to dive a little deeper into the 3 D’s

Community News2 weeks ago

Community News2 weeks ago

Community News1 week ago

Community News1 week ago

Community News1 week ago

Community News1 week ago

Community News1 week ago

Community News1 week ago

Community News2 weeks ago

Community News2 weeks ago

Community News1 week ago

Community News1 week ago

Community News2 weeks ago

Community News2 weeks ago

Community News1 week ago

Community News1 week ago